We recently wrote about the opportunity zones incentive  and the benefits it could provide for Vermont communities, investors, and developers. While we await the IRS regulations governing the mechanics of opportunity zone investing, we thought it would be a good time to examine how state planning law might affect potential opportunity fund financed projects.

and the benefits it could provide for Vermont communities, investors, and developers. While we await the IRS regulations governing the mechanics of opportunity zone investing, we thought it would be a good time to examine how state planning law might affect potential opportunity fund financed projects.

Vermont has unique land use and planning laws that can feel burdensome. However, a thoughtful strategy can lessen the burden, and understanding that Vermont’s state-wide land use laws have a clear goal—to concentrate and encourage development in compact traditional centers—can be used to a project’s advantage. In many cases, this goal overlaps neatly with the opportunity zone program, as the state-nominated zones generally coincide with traditional population centers where development is encouraged. Developers who understand and are able to design real estate projects that take advantage of the State’s land-use laws will be able to maximize the potential of opportunity zone financing, available public financial incentives, and the many social benefits that the program is intended to create.

This blog post provides a quick primer on the key Vermont land use laws and programs that may be utilized to enhance opportunity zone financed real estate development projects, and then summarizes the applicability of each planning program in the 25 designated opportunity zones.

Act 250

Passed in 1970, Act 250 is a state-wide land use control that overlays local zoning regulation. Developments and subdivisions that exceed various size thresholds trigger Act 250 jurisdiction and require a land use permit. To receive a land use permit, a developer needs to conform with the ten Act 250 criteria, which ensure projects meet environmental standards and encourage smart growth to protect public infrastructure and meet state, regional, and local planning goals.

How Act 250 might impact a project varies widely depending on the location and the project’s fit within the surrounding land uses. However, permits are granted for 98% of applications, so a well-planned project is likely to go through. Instead of focusing on the specifics of Act 250, this blog examines some of the exceptions and programs that streamline the process. For more information on Act 250, visit the Natural Resource Board website.

Vermont’s state land use goal is to continue the traditional pattern of compact population centers surrounded by working agricultural and forest land. Thus, exceptions and incentives to the Act 250 process promote that pattern and “funnel” development into existing centers. The two tools we consider are the state designation programs and priority housing.

State Designation Programs

The designation programs are a tool for municipalities to determine where to concentrate growth and then align various state taxing and permitting policies to promote growth in that area. Three “core” designations—downtowns, village centers, and new town centers—establish the highest density district in the municipality and receive the most benefits. Two “add-on” designations—neighborhood development areas and growth centers—are available once a municipality has a core district. The add-on designations support growth in the core district and encourage smart growth principles throughout the town. Designated areas may be layered to stack benefits.

Each designation receives a different suite of benefits. In existing centers—downtowns and village centers—the benefits center around substantial tax credits to offset renovation costs to modernize historic buildings. All the designations receive some form of Act 250 permit streamlining and reduced application costs. Downtowns receive the greatest combination of benefits, while new town centers receive the least benefits. Municipalities also receive priority access to state grants for smart growth infrastructure and planning (more information on state designation programs here, and a summary of benefits for each designation).

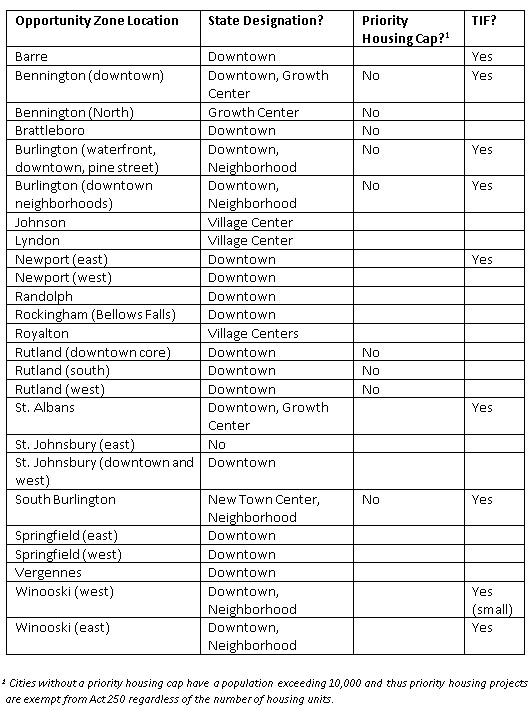

The table below lists all of designated areas within each opportunity zone. By developing an opportunity zone project in a designated area, a developer will be able to reap the many benefits associated with the designation. Note that the downtowns and village centers in the smaller cities and town usually occupy only a portion of the opportunity zone. Burlington, South Burlington, and St. Albans all have excellent overlap with a designated area covering most of the corresponding opportunity zone.

Priority Housing Projects

Often land use controls work against workforce and affordable housing. To combat this, the State has exempted priority housing projects from Act 250 jurisdiction. Typically, an Act 250 permit is needed when building a housing project with 10 or more units, on one tract of land or nearby tracts. Priority housing projects raise this threshold depending on the municipality’s population. The threshold ranges from 25 units for a town of 3,000 or less to an unlimited cap once the population exceeds 10,000.

The state designation areas are a prerequisite to the exemption. A priority housing project must be within a designated area. Furthermore, village centers do not qualify for priority housing unless they are also a designated neighborhood. The final prerequisite is the nature of the housing. The project must supply “mixed-income” housing—where 20% or more of the units constitute affordable housing (similar but different criteria exist when the housing is owner-occupied). Most priority housing projects can also be “mixed-use,” where up to 60% of the floor area is used for commercial or community space, so long as the housing is mixed-income. In designated neighborhoods, mixed-use is not allowed.

Including priority housing in an opportunity zone financed development project is accordingly an attractive way to streamline the development process and take advantage of downtown tax credits, while at the same time helping to alleviate the Vermont’s shortage of affordable housing.

Tax Increment Financing

Developers and investors are likely familiar with tax increment financing (TIF) districts that help cities and towns debt-fund infrastructure to support new development. Although the likelihood of new TIF districts in Vermont is uncertain, many opportunity zones have preexisting TIF districts. These preexisting districts may provide room for additional development without the need for developers to cover associated infrastructure costs.

Conclusion

To conclude, many opportunity zone real estate development projects should be able to take advantage of the State’s designation programs, the priority housing program and/or tax increment financing. The combined advantages of utilizing these State programs, plus the economic benefits of an opportunity zone financed project, promises to ease development burdens, especially for projects with affordable housing components, in Vermont’s population centers.